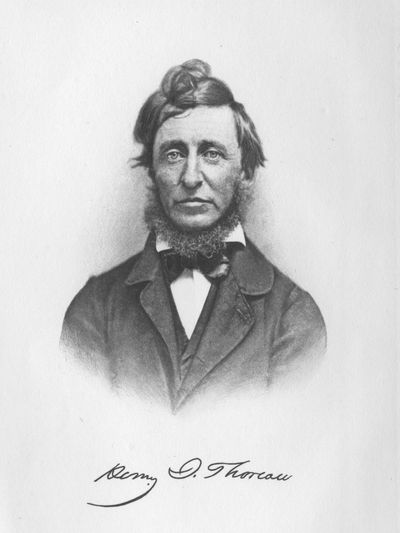

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

"I am a mystic, a transcendentalist & a natural philosopher to boot." H.D. Thoreau, 1853

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I wrote the following biographical sketch of Thoreau during the period of time when my connection with him was at its strongest. It reflects the clarity that I was experiencing in my understanding of him at that time and emphasizes the message he most wanted me to convey. It was originally posted on this website and later included in my book, The Thoreau Whisperer. - Cathryn McIntyre (2020)

Henry David Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts on July 12, 1817. He was the third of four children of John Thoreau and Cynthia Dunbar. Other than the first few years of his life, Thoreau spent his entire life living in Concord. He said of it, "I have never got over my surprise that I should have been born into the most estimable place in all the world, and in the very nick of time, too."

There are few men who live who achieve the greatness of this man known as Henry David Thoreau. It was not so much seen or known within the course of his life, but in the words that survived him and that have been read and reflected upon by so many. That is because there is within each of his observations of the world the purest truth and it is a truth that stems from his understanding of spirit.

This man in his life was not so well adept, that is if we judge him in the common way that humans are often judged, by their physical appearance or their material accomplishments, but what of their moral accomplishments? What of the factor of honor and integrity in their lives? What of the deepest and most important tie that binds us to our source and to each other? What of spirit? In this regard, we cannot overestimate Thoreau's value because of the strength and power of his words, because the truest of all truths will be found in the words of Thoreau.

For those who have never read Thoreau's work and who consider it best left in the hands of the academics, I encourage you to read him for when you do you will find that the heart of his message is a simple one. Do with less, want for less, because when you are in touch with your truest self you will see that you have all that you need and that all that you are is permanent and everlasting. The spirit in you does not wear down the way the body wears down. It does not lose color or diminish in strength. It stays strong and steady and when the body reaches its end the spirit casts itself back into the light from whence it came where it is renewed and reinvigorated and sets out to create again.

Henry David Thoreau attended Harvard College in Cambridge from 1833-1837. While there he read the essay Ralph Waldo Emerson called, Nature. It was an essay that described a philosophy called transcendentalism and to Thoreau it was an articulation of his own knowledge and experience. It was through the purity and truth in nature that Thoreau had first felt the stirrings of his own soul.

After returning to Concord in 1837, Thoreau met Emerson for the first time and that meeting between Emerson, who was a sage at 34 and Thoreau, who was then only 20, marked the beginning of an extraordinary association. It was Emerson who recommended Thoreau keep a journal; it was Emerson who encouraged Thoreau to write and who helped to get his early essays and poems placed in the publication called The Dial; and it was Emerson who gave Thoreau permission to build a cabin on a piece of land that he owned at Walden Pond.

Thoreau's masterpiece, Walden or Life in the Woods, was published in 1854, and was enough to establish him as a writer during his lifetime. In the last few years of his life he was frequently visited by those who had read Walden and wished to know the author. In addition to Walden, and his extensive journals that are felt by some to be his greatest accomplishment, Thoreau wrote other books, poems and essays and delivered lectures on the issues of his day. His best known essay, Civil Disobedience, was inspired by a dispute over taxes that led to a night in the Concord jail. He also wrote essays and spoke out powerfully for the abolition of slavery and against the government that supported it; he spoke out for the rights of the individual over the demands of any government because he felt the only laws that should govern any man were the divine laws; and he spoke of the ability of man to intuit his own right actions through his conscience, which is a direct connection to the divine.

Thoreau passed into spirit on May 6, 1862, another victim of tuberculosis, or what was called consumption, the disease that had taken the lives of so many in the 19th century, and yet two centuries later, his words, his wisdom and his spirit endure.

------------------------

© Copyright 2008, Cathryn McIntyre, All rights reserved

© Copyright 2018, published in The Thoreau Whisperer by Cathryn McIntyre

Not to be copied or reproduced in any form without written consent.

THOREAU'S WORK

THE WRITTEN WORKS OF HENRY DAVID THOREAU

This is a list of Thoreau's best known books, essays and poems. Please refer to websites for The Thoreau Institute/Walden Woods Project or The Thoreau Society for a more complete list of his written works

Books

A Week on the Concord and Merrimac Rivers (1849)

Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854)

The Maine Woods (1864)

Cape Cod (1865)

A Yankee in Canada (1866)

Unfinished manuscripts (posthumously published)

Edited and published by Thoreau scholar,

Bradley P. Dean, Ph.D.

Faith in a Seed (1993)

Wild Fruits (1999)

Letters to a Spiritual Seeker (2004)

Best Known Essays

After the Death of John Brown (1860)

Autumnal Tints (1862)

Civil Disobedience (a/k/a Resistance to Civil Government) (1849)

The Last Days of John Brown

Life Without Principle (1854)

Natural History of Massachusetts (1842)

A Plea for Captain John Brown (1860)

Slavery in Massachusetts (1854) The Succession of Forest Trees (1860)

A Walk to Wachusett (1843)

Walking (1862)

Wild Apples (1862)

Best Known Poems

The Inward Morning (1842)

Free Love, (1842)

The Poet's Delay, (1842)

Rumors from an Æolian Harp (1842)

Friendship

The Old Marlborough Road

Sic Vita

Sympathy

THOREAU QUOTES

Quotes from Thoreau's Journal

Thoreau began a journal at the suggestion of his friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson on October 22, 1837. Thoreau was just 20 at the time and his journal writing continued for the rest of his life. His first entry began with this: "What are YOU doing now?" he asked. "Do you keep a journal?" So I make my first entry..."

From Thoreau's Journal

"If with closed ears and eyes I consult consciousness for a moment – immediately are all walls and barriers dissipated – earth rolls from under me, and I float, by the impetus derived from the earth and the system – a subjective – heavily laden thought, in the midst of an unknown & infinite sea, or else heave and swell like a vast ocean of thought – without rock or headland. Where are all riddles solved, all straight lines making there their two ends to meet – eternity and space gamboling familiarly through my depths. I am from the beginning – knowing no end, no aim. No sun illumines me, – for I dissolve all lesser lights in my own intenser and steadier light - I am a restful kernel in the magazine of the universe."

- H.D. Thoreau, Journal, August 1838

"Methinks my present experience is nothing; my past experience is all in all. I think that no experience which I have to-day comes up to, or is comparable with, the experiences of my boyhood. And not only this is true, but as far back as I can remember I have unconsciously referred to the experiences of a previous state of existence. “For life is a forgetting,” etc. Formerly, methought, nature developed as I developed, and grew up with me. My life was ecstasy. In youth, before I lost any of my senses, I can remember that I was all alive, and inhabited my body with inexpressible satisfaction; both its weariness and its refreshment were sweet to me. This earth was the most glorious musical instrument, and I was audience to its strains. To have such sweet impressions made on us, such ecstasies begotten of the breezes! I can remember how I was astonished. I said to myself, — I said to others, — “There comes into my mind such an indescribable, infinite, all-absorbing, divine, heavenly pleasure, a sense of elevation and expansion, and [I] have had nought to do with it. I perceive that I am dealt with by superior powers. This is a pleasure, a joy, an existence which I have not procured myself. I speak as a witness on the stand and tell what I have perceived.” The morning and the evening were sweet to me, and I led a life aloof from the society of men. I wondered if a mortal had ever known what I knew. I looked in books for some recognition of a kindred experience, but, strange to say, I found none. Indeed, I was slow to discover that other men had had this experience, for it had been possible to read books and to associate with men on other grounds. The maker of me was improving me. When I detected this interference I was profoundly moved. For years I marched as to a music in comparison with which the military music of the streets is noise and discord. I was daily intoxicated, and yet no man could call me intemperate. With all your science can you tell how it is and whence it is that light comes into the soul?" H.D. Thoreau, Journal, July 16, 1851

"The question is not what you look at, but what you see."

H.D. Thoreau, Journal, August 5, 1851

"Carlyle said that how to observe was to look, but I say that it is rather to see, and the more you look the less you will observe. "

H.D. Thoreau, Journal, September 13, 1852

"I felt that it would be to make myself the laughing-stock of the scientific community to describe to them that branch of science which specially interests me, in as much as they do not believe in a science which deals with the higher law. So I was obliged to speak to their condition and describe to them that poor part of me which alone they can understand. The fact is I am a mystic, a transcendentalist, and a natural philosopher to boot. Now I think of it, I should have told them at once that I was a transcendentalist. That would have been the shortest way of telling them that they would not understand my explanation." H.D. Thoreau, Journal, March 5, 1853

"I love nature partly because she is not man, but a retreat from him.

None of his institutions control or pervade her. There a different kind of right prevails. In her midst I can be glad with an entire gladness. If this world were all man, I could not stretch myself, I should lose all hope. He is constraint, she is freedom to me. He makes me wish for another world. She makes me content with this." H.D. Thoreau, Journal, January 3, 1853

"I thrive best on solitude. If I have had a companion only one day in a week, unless it were one or two I could name, I find that the value of the week to me has been seriously affected. It dissipates my days, and often it takes me another week to get over it." - H.D. Thoreau, Journal, December 28, 1856

"Many an object is not seen, though it falls within the range of our visual ray, because it does not come within the range of our intellectual ray, i.e. we are not looking for it. So, in the largest sense, we find only the world we look for." - H.D. Thoreau, Journal, July 2, 1857

"Many college text-books which were a weariness and a stumbling-block when studied, I have since read a little in with pleasure and profit." - H.D. Thoreau, Journal, February 19, 1854

"It is only when we forget all our learning that we begin to know."

H.D. Thoreau, Journal, October 4, 1859

"Talk about slavery! It is not the peculiar institution of the South. It exists wherever men are bought and sold, wherever a man allows himself to be made a mere thing or a tool, and surrenders his inalienable rights of reason and conscience. Indeed, this slavery is more complete than that which enslaves the body alone. "

H.D. Thoreau, Journal, December 4, 1860

THOREAU QUOTES

Quotes from Thoreau's Walden

"I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. . . . In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness."

- H.D. Thoreau, Walden, 1854

"With thinking we may be beside ourselves in a sane sense. By a conscious effort of the mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent. We are not wholly involved in Nature. I may be either the driftwood in the stream, or Indra in the sky looking down on it. I may be affected by a theatrical exhibition; on the other hand, I may not be affected by an actual event which appears to concern me much more. I only know myself as a human entity; the scene, so to speak, of thoughts and affections; and am sensible of a certain doubleness by which I can stand as remote from myself as from another. However intense my experience, I am conscious of the presence and criticism of a part of me, which, as it were, is not a part of me, but spectator, sharing no experience, but taking note of it, and that is no more I than it is you. When the play, it may be the tragedy, of life is over, the spectator goes his way. It was a kind of fiction, a work of the imagination only, so far as he was concerned. This doubleness may easily make us poor neighbors and friends sometimes." - H.D. Thoreau, Walden, 1854

"Men frequently say to me, "I should think you would feel lonesome down there, and want to be nearer to folks, rainy and snowy days and nights especially." I am tempted to reply to such,—This whole earth which we inhabit is but a point in space. How far apart, think you, dwell the two most distant inhabitants of yonder star, the breadth of whose disk cannot be appreciated by our instruments? Why should I feel lonely? is not our planet in the Milky Way? This which you put seems to me not to be the most important question. What sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary? I have found that no exertion of legs can bring two minds much nearer to one another."

- H.D. Thoreau, Walden, 1854

"The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star. "

- H.D. Thoreau, Walden, 1854

THOREAU QUOTES

From The Maine Woods, Khatadin

"Perhaps I most fully realized that this was primeval, untamed, and forever untameable Nature, or whatever else men call it, while coming down this part of the mountain. We were passing over "Burnt Lands," burnt by lightning, perchance, though they showed no recent marks of fire, hardly so much as a charred stump, but looked rather like a natural pasture for the moose and deer, exceedingly wild and desolate, with occasional strips of timber crossing them, and low poplars springing up, and patches of blueberries here and there. I found myself traversing them familiarly, like some pasture run to waste, or partially reclaimed by man; but when I reflected what man, what brother or sister or kinsman of our race made it and claimed it, I expected the proprietor to rise up and dispute my passage. It is difficult to conceive of a region uninhabited by man. We habitually presume his presence and influence everywhere. And yet we have not seen pure Nature, unless we have seen her thus vast and dread and inhuman, though in the midst of cities. Nature was here something savage and awful, though beautiful. I looked with awe at the ground I trod on, to see what the Powers had made there, the form and fashion and material of their work. This was that Earth of which we have heard, made out of Chaos and Old Night. Here was no man's garden, but the unhandselled globe. It was not lawn, nor pasture, nor mead, nor woodland, nor lea, nor arable, nor waste-land. It was the fresh and natural surface of the planet Earth, as it was made for ever and ever, — to be the dwelling of man, we say, — so Nature made it, and man may use it if he can. Man was not to be associated with it. It was Matter, vast, terrific, — not his Mother Earth that we have heard of, not for him to tread on, or be buried in, — no, it were being too familiar even to let his bones lie there, — the home, this, of Necessity and Fate.

There was there felt the presence of a force not bound to be kind to man. It was a place for heathenism and superstitious rites, — to be inhabited by men nearer of kin to the rocks and to wild animals than we. We walked over it with a certain awe, stopping, from time to time, to pick the blueberries which grew there, and had a smart and spicy taste. Perchance where our wild pines stand, and leaves lie on their forest floor, in Concord, there were once reapers, and husbandmen planted grain; but here not even the surface had been scarred by man, but it was a specimen of what God saw fit to make this world.

What is it to be admitted to a museum, to see a myriad of particular things, compared with being shown some star's surface, some hard matter in its home! I stand in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound has become so strange to me. I fear not spirits, ghosts, of which I am one, — that my body might, — but I fear bodies, I tremble to meet them. What is this Titan that has possession of me? Talk of mysteries! — Think of our life in nature, — daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it, — rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! The solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?"

- Henry David Thoreau, The Contact Passage, The Maine Woods, Katahdin 1848

THOREAU QUOTES

From his essay, Walking

"I took a walk on Spaulding’s Farm the other afternoon. I saw the setting sun lighting up the opposite side of a stately pine-wood. Its golden rays straggled into the aisles of the wood as into some noble hall. I was impressed as if some ancient and altogether admirable and shining family had seated there in that part of the land called Concord, unknown to me; to whom the Sun was servant; who had not gone into society in the village; who had not been called on. I saw their park, their pleasure ground, beyond through the wood, in Spaulding’s cranberry meadow. The pines furnished them with gables as they grew. Their house was not obvious to vision; the trees grew through it. I do not know whether I heard the sounds of a suppressed hilarity or not. They seemed to recline on the sunbeams. They have sons and daughters. They are quite well. The farmer’s cart path which leads directly through their hall does not in the least put them out, — as the muddy bottom of a pool is sometimes seen through the reflected skies. They never heard of Spaulding, and do not know that he is their neighbor, — notwithstanding that I heard him whistle as he drove his team through the house. Nothing can equal the serenity of their lives. Their coat of arms is simply a lichen. I saw it painted on the pines and oaks. Their attics were in the tops of the trees. They are of no politics. There was no noise of labor. I did not perceive that they were weaving or spinning. Yet I did detect, when the wind lulled and hearing was done away, the finest imaginable sweet musical hum, — as of a distant hive in May, which perchance was the sound of their thinking. They had no idle thoughts, and no one without could see their work, for their industry was not as in knots and excrescences embayed.

But I find it difficult to remember them. They fade irrevocably out of my mind even now that I speak and endeavor to recall them, and recollect myself. It is only after a long and serious effort to recollect my best thoughts that I become again aware of their cohabitancy. If it were not for such families as this I think I should move out of Concord." - Henry David Thoreau, Walking

SLEEPY HOLLOW CEMETERY

The Thoreau Family Plot at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, MA

Henry David Thoreau passed at his home on Main Street in Concord, Massachusetts on May 6, 1862. He was not yet 45 years old. Thoreau's funeral service was held at First Parish Church in Concord, Massachusetts on May 9, 1862. His body was buried at Concord's Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, first in the older section of the cemetery near the graves of his grandparents. Later it was moved for reburial on the hillside known as Author's Ridge. The Thoreau family plot, pictured above, is the first that you see when you climb up the steep ascent to the ridge. The Alcott plot is immediately to the left of the Thoreau plot and the Hawthorne plot across from the Alcott's. The Emerson family plot is a short distance away. In the photograph above, Thoreau's grave is the far left of the picture, the one with all the pinecones and other tokens of remembrance left behind. It is not unusual to find pencils and walking sticks left on the grave and occasionally a copy of Walden.

The following are excerpts taken from Ralph Waldo Emerson's eulogy for Thoreau that was delivered at First Parish Church in Concord, MA on May 9, 1862.

The scale on which his studies proceeded was so large as to require longevity, and we were the less prepared for his sudden disappearance. The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost. It seems an injury that he should leave in the midst of his broken task which none else can finish, a kind of indignity to so noble a soul that he should depart out of Nature before yet he has been really shown to his peers for what he is. But he, at least, is content. His soul was made for the noblest society; he had in a short life exhausted the capabilities of this world; wherever there is knowledge, wherever there is virtue, wherever there is beauty, he will find a home.

* * *

I think his fancy for referring everything to the meridian of Concord did not grow out of any ignorance or depreciation of other longitudes or latitudes, but was rather a playful expression of his conviction of the indifferency of all places, and that the best place for each is where he stands. He expressed it once in this wise: "I think nothing is to be hoped from you, if this bit of mould under your feet is not sweeter to you to eat than any other in this world, or in any world."

* * *

Presently he heard a note which he called that of the night-warbler, a bird he had never identified, had been in search of twelve years, which always, when he saw it, was in the act of diving down into a tree or bush, and which it was vain to seek; the only bird which sings indifferently by night and by day. I told him he must beware of finding and booking it, lest life should have nothing more to show him. He said, "What you seek in vain for, half your life, one day you come full upon, all the family at dinner. You seek it like a dream, and as soon as you find it you become its prey."

Copyright © 2023 The Concord Writer - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder